The Minneapolis Fed Should Start Paying Closer Attention To Goldman Sachs Research

Understanding why people returned to work after the pandemic is easy. Foreseeing the soft landing was a bit more difficult, but there were some who did it.

Last week, the Minneapolis Star Tribune published an article on the U.S. economy entitled “Getting So Many Mixed Signals” centered around an interview with Neel Kashkari, president of the Minneapolis Fed.

In the article, Kashkari noted not only how uniquely uncharted and challenging the current economic backdrop is these days but also how difficult it is to get our bearings given the plethora of conflicting economic data signals these days. “Right now, we are getting so many mixed signals and things are reacting differently that we had expected.”

While rightly acknowledging, long after the fact, that soaring, covid-era inflation was the result of a massive supply shock and therefore transitory (albeit lasting longer than many expected), he admitted that, “We weren’t able to diagnose the high inflation when it hit us. And then we didn’t do a very good job of diagnosing why it stayed high for as long as it did. And now, we’ve been surprised at how quickly it’s come down in the past six months.”

Not very reassuring, to say the least. But even more unsettling (and shocking) is the answer Kashkari gave to the following question:

Q: Why did labor supply bounce back so much? Initially there was a lot of uncertainty if workers who left the labor market during the pandemic would ever return.

A: We don’t know fully.Immigration is definitely playing a role. But I also think it’s just Americans want to work. And maybe it’s the inflation, that people are saying, ‘Oh my gosh, prices are going up, I need to work just to try to keep my head above water.’ Some of those retirees, maybe they went back to work part-time. Maybe remote work opened some possibilities for some folks. Maybe all of the above.

What? Seriously?!

WTF?!?!

We most certainly do know, fully, why labor supply bounced back so much.

I cannot imagine a worse, more alarming answer to that question from someone in Kashkari’s position. In and around monetary policy, no set of topics in the past decade or so has been more critical, more scrutinized, or more analyzed than the covid-era job market, the supply shock set off by the pandemic, and how and why we’ve come through it more successfully than any other economy in the world.

The only answer to the question posed to Kashkari about why labor supply bounced back so much, the ONLY answer, is that employers, desperate beyond belief to get people back to work to meet the insane, insatiable demand of consumers and businesses alike, raised wages quickly, aggressively, and repeatedly. That’s it. It’s really that simple - basic supply and demand curves taught in every single Econ 101 class.

Raise your bid sufficiently until your offering price crosses over enough people’s ask and people will say yes to a mutually agreeable price. While the job market can be phenomenally complicated, undoubtedly one of Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects, it is, nonetheless, at its core, still just a market, and markets have buyers and sellers that consummate transactions when they reach a mutually agreeable price.

As we wrote month after month at the time, beginning in 2021, there was an enormous bid-ask spread between employers and employees around what it would take to get people to return to their pre-pandemic jobs. As soon as employers realized that workers weren’t going to budge an inch to bridge that gap, they caved to essentially every single demand from workers - starting first and foremost with wages but also benefits, remote work, health and safety concerns, work-life balance, corporate culture, career paths, training and development, and every other single thing that employees were demanding.

Quits skyrocketed (along with wage inflation and then, as a result, broader inflation) as huge chunks of the workforce switched employers, changed careers, left the workforce, and reassessed and reprioritized major aspects of their lives. But as employers capitulated to worker demands, the bid-ask spread eventually narrowed sufficiently, people returned to work, the job market moved into greater and greater equilibrium, and monthly job gains soared.

Everybody should know this story by now. Fully. This isn’t peering into the crystal ball trying to forecast the future - it’s looking into the rearview mirror to accurately assess what’s already happened. This is lay-up stuff.

What is arguably the more difficult part of the Covid-era economic story is the soft landing - inflation having dropped to target levels with no rise in unemployment.

While the soft landing has now become the consensus view looking forward (laughable given that it’s already occurred), how and why it came about remains a mystery to most, a subject of enormous debate among a few, and an object of scorn and derision among plenty who refuse to acknowledge not only that it happened but that it ever will or even ever could.

But here again, the answer is not overly complicated and it’s based on the same underlying dynamics of how the job market works combined with what, fundamentally, was going on during the Covid era.

Going back to why labor demand bounced back so much, the key to the soft landing is recognizing that the bid-ask spread narrowed gradually over time. As the economy opened up once vaccination rates started climbing, the flood-gates opened up on unprecedented pent-up demand for travel and vacations, entertainment, going out to eat, shopping, and every other service imaginable.

This insane demand, on top of the enormous demand that had already materialized for all the goods people were trying to buy during lock-down, led employers to start raising wages to get people back to work in order to meet this demand.

So employers raised wages a bit (and made workplaces safe, increased benefits, allowed people to work remotely, and said yes to basically whatever else candidates asked for), some job openings with better salaries got filled, the economy inched back to life, people switched to better, higher-paying jobs and started spending again, and consumer, business, and labor demand persisted as payrolls grew and the economy came back to life.

Employers then posted more job openings and raised wages a little bit more to fill those openings to meet the seemingly endless demand. A few more candidates took the better paying jobs, and they, in turn, started spending their better wages, causing the cycle to begin yet again.

This same exact cycle would play out over and over again across the entire economy for the next three years.

Along the way and especially early on, because demand was so much greater than supply, companies raised the prices of their goods and services, first and foremost because they could, but also because their own costs were going up. Businesses everywhere were being forced to raise their labor costs in order to staff their business lest they risk going out of business altogether, and as companies raised prices, their customers’ costs went up, too.

So the massive supply shock brought on by the pandemic resulted in a huge spike in inflation, but that inflation (at least the wage and salary component) was what eventually brought supply and demand back into equilibrium because the increase in wages and salaries brought people back into the workforce.

Like a fever, the symptom of the illness was also its cure.

Rising wages eventually resulted in job growth sufficient enough to sate demand - initially just labor demand but that then, in turn, eventually resulted in a sufficiently large workforce across the country to quell the anomalous, outsized demand for goods and services as things finally started returning to normal.

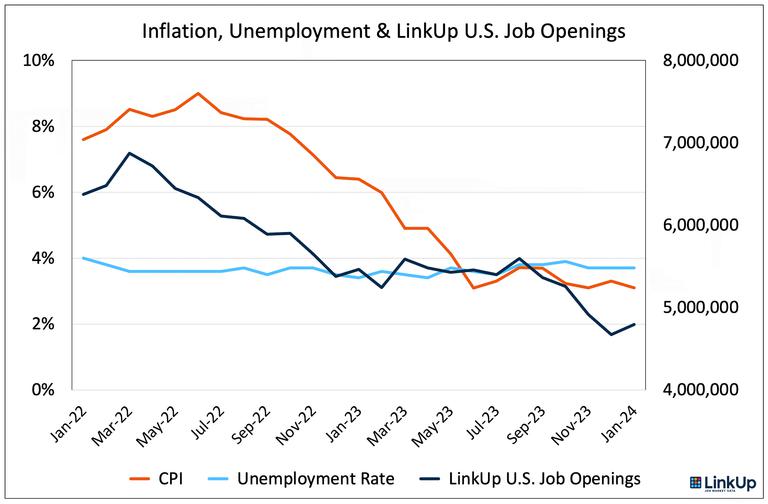

So the key to recognizing the soft landing was accurately assessing labor demand.

As the chart above shows, labor demand subsided as businesses started to reach the point where they had the employees they needed to meet consumer and business demand. Declining labor demand, as evidenced by fewer and fewer job openings on company and employer websites around the country (that’s what constitutes LinkUp’s highly unique, highly accurate job market dataset), was not a sign of a weakening economy (which it can be under different circumstances) but rather a sign that the economy as a whole was moving toward greater and greater equilibrium.

And as the job market came into greater and greater balance, companies slowed their hiring, posted fewer and fewer job openings on their corporate career portal on their own company website, and, for the most part, stopped raising wages. After a period of time, largely as a result of declining wage inflation, broader inflation started to drop, too, and the soft landing was underway.

In exhaustive detail, we highlighted the criticality of job openings in a blog post in September, 2022 - a particularly intense period of peak inflation hysteria where widespread doomsday scenarios ranged between whether a severe recession or an outright depression, lasting years in either case, was going to be required to get inflation under control.

In that blog post entitled “It’s Now Just Job Vacancies. The Rest Is Noise” we summarized the general state of the economy and the job market, noting the normalization that was well underway and the increasing equilibrium we were seeing in the job market.

Specifically, we laid out the case that job openings stood as the key to understanding the soft landing that was already occurring and that we fully expected to see continuing until inflation returned to normal with no rise in unemployment.

I’d highly recommend to anyone interested in understanding the U.S. economy and/or the job market to read the entire post, but I’ll include here the key takeaway:

So while it’s the current era’s rapid recovery amid supply issues (along with a war and corporate price-gouging) that have driven up inflation, demand reduction (hopefully not demand destruction) will be the vehicle by which the Fed restores balance. And as noted previously, the Fed is solely focused on reducing labor demand, ideally through a soft landing – a decline in job openings rather than an increase in unemployment. As a result, the Fed is lasered in on job vacancies as the most critical gauge in the war on inflation.

During the Fed Chair’s press conference following the [most recent] FOMC rate hike, there was this exchange:

RACHEL SIEGEL [Washington Post]: Are vacancies still at the top of your list in terms of understanding the labor market?

CHAIR POWELL: Yes

So job vacancies are all that matters – they are the single most potent metric that captures the balance between supply and demand in the labor market. Everything else is either a secondary, lagging consequence of the imbalance between labor demand and supply (job growth, wage growth, unemployment rate, unemployment filings, etc.) or a tertiary indicator of the inner-workings deep under the hood of the nation’s job market engine (labor force participation rate, employment population ratio, quits, etc.).

As Jan Hatzius, Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs, noted on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast in August [of 2022]:

“The big issue on inflation is labor market imbalance and job vacancies are the key to understanding labor market imbalance. If I had defined Full Employment a year and a half ago, I would have talked about unemployment rate and employment population ratio but open positions would have only had a supporting role. Now, job openings are playing a much more central role because they basically give you the balance between total labor demand and total labor supply.”

As Jan Hatzius, Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs, noted on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast in August [of 2022]:

The big issue on inflation is labor market imbalance and job vacancies are the key to understanding labor market imbalance. If I had defined Full Employment a year and a half ago, I would have talked about unemployment rate and employment population ratio but open positions would have only had a supporting role. Now, job openings are playing a much more central role because they basically give you the balance between total labor demand and total labor supply.

Jan Hatzius, Chief Economist

Goldman Sachs

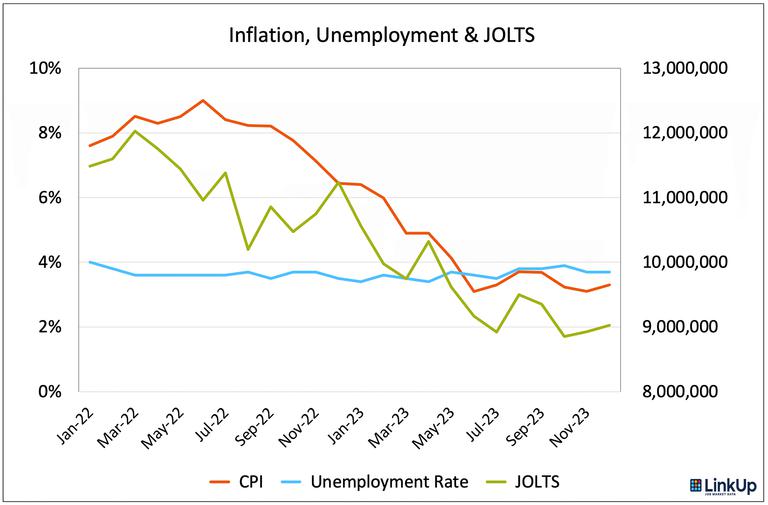

So job openings were (and still are), unequivocally, the key barometer of equilibrium in the job market and the economy as a whole. But that barometer must be accurate and unfortunately, most people, if they’re even paying attention to job openings, still look(ed) to the Bureau of Labor Statistics JOLTS survey as the best measure of job openings in the country. What a mistake.

We’ll dig into the myriad flaws pervasive in JOLTS data, but suffice it to say for now that it’s inaccurate, horribly lagged, frequently revised, and getting worse as survey response rates continue to plummet.

Looking at the chart below, it’s clear that the JOLTS data did eventually get to approximately the same place as LinkUp’s data (which, by the way, is accurate and now-casted daily), but it certainly took a circuitous, bumpy route to get there, to say the least.

For much of 2022, JOLTS numbers were actually rising right at the precise, most crucial moment where the job market was actually starting to move into greater and greater equilibrium and actual, real job openings across the U.S. sourced directly from employer websites around the world were declining.

There is no way that anyone looking at JOLTS data then or now could get a sense of the soft landing that we (and a handful of others) were seeing in real-time with our data.

As we noted above, Jan Hatzius, Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs, was one of those who were seeing what we were seeing, in part because he and his team had pretty much disregarded JOLTS data entirely, incorporating into their models instead a blended average of LinkUp and Indeed data.

For anyone who missed it, Jan had a really nice, much deserved write-up in the Journal just last week, highlighting both Jan’s brilliant analysis and his stellar track-record over the past 15 years in making a ton of hugely prescient calls.

Maybe the Minneapolis Fed should start paying closer attention to Goldman’s research and/or job market data companies in their own backyard.

Insights: Related insights and resources

-

Blog

02.21.2024

Follow the Job Data, Not the Headlines

Read full article -

Blog

02.20.2024

Big Software Push at Disney

Read full article -

Blog

02.16.2024

Mapping the AI Revolution with LinkUp (Part III)

Read full article -

Blog

02.15.2024

Disney's Tech Listings on the Rise

Read full article -

Blog

02.14.2024

LinkUp Forecast: January JOLTS report by the BLS

Read full article

Stay Informed: Get monthly job market insights delivered right to your inbox.

Thank you for your message!

The LinkUp team will be in touch shortly.