LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of 850,000 Jobs In May 2021

In the midst of enormous complexity, magnitude, impact, and polarization, the ferocity of the debate around the factors impacting the labor market is as elevated as the level of uncertainty around where precisely the labor market actually is these days.

It’s not surprising in the least given how utterly unprecedented everything has been of late, but at no point in the past 20 years has focus on the labor market been so intense. And because we are in such uncharted territory in the midst of enormous complexity, magnitude, impact, and polarization, the ferocity of the debate around the factors impacting the labor market is as elevated as the level of uncertainty around where precisely the labor market actually is these days.

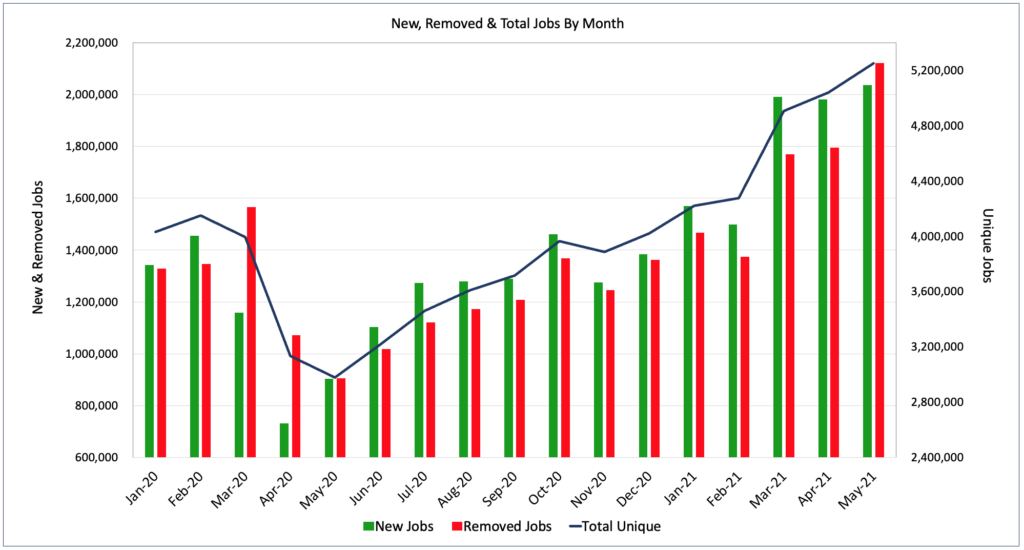

Of course, the backdrop is one of rapid recovery and strong job growth as vaccination rates rise, the economy opens up, consumers start spending again, and businesses start hiring to meet growing demand. Since the beginning of the year, job openings in the U.S. indexed from company websites globally have risen 25% and new job listings have risen 30%. Even more significantly, the number of jobs removed from company and employer websites has risen 45% (companies tend to be quite disciplined about quickly removing job openings from their company website once they’ve filled the opening with a hire).

During the past 5 months, the U.S. economy has added a net gain of 1.8 million jobs (according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics), ‘official’ unemployment has dropped to 6.1%, and just last week, unemployment claims fell to 406,000 – the 4th consecutive ‘low-water’ market since the pandemic began.

But beyond that baseline set of facts, virtually every other aspect of the recovery is being hotly debated by economists, pundits, politicians, businesses, and the media. While there are some ancillary debates taking place at the margins, the primary point of contention centers around the relationship between labor demand and job growth and the extent to which an imbalance there (real or perceived, broad or narrow, temporary or permanent, etc.) will lead to sustained, problematic rates of inflation.

The debate reached fever pitch last month when the Department of Labor reported April job gains of just 266,000 jobs, well below what everyone thought would be another strong jobs report (ourselves included). But while we tend to take a more measured view of any single monthly jobs report (taking the long view, trusting our own job market data, and relying on our 20+ year understanding of the labor market), a national freak-out erupted, characterized by a May 6th WSJ headline, “Millions Are Unemployed. Why Can’t Companies Find Workers?“.

Of course the article points first to the obvious pandemic-related culprits as to why job growth was so low last month – people are afraid of returning to work due to Covid and many have to stay home to take care of children. But the article adds two additional factors: excessively generous unemployment benefits and a pervasive skills gap in the workforce – both of which absolve employers for any responsibility for the jobs numbers and place it, instead, on the government and job seekers.

While Covid-related factors are most definitely material (albeit temporary) factors in the job market’s recovery, unemployment benefits are at best, peripheral, and the skills gap, while real from a deeper and longer-term perspective, has little to no impact on short-term, nation-wide job gains across the entire economy.

Beyond Covid-related factors, the primary contributor to spotty job gains is a pervasive and persistent unwillingness among employers to raise wages. And that factor is mentioned almost only in passing in the WSJ article, with low pay cited not so much as a contributor to the supply/demand imbalance but more along the lines of wage inflation being a nasty outcome of the supply/demand imbalance.

Still, the shortage threatens to restrain what is otherwise shaping up to be a robust post-pandemic economic recovery. Some businesses are forgoing work, such as not bidding on a project, delivering parts more slowly or keeping a section of the restaurant closed. That reduces the pace of the economy’s expansion. Other companies are raising wages to attract employees, which could inflate prices for customers or reduce profit margins for owners.

Having been firmly situated in the middle of the job market for the past 20 years, literally as a market maker between employers and job seekers, and now bearing witness from such a perch to a 3rd economic recovery, I can say quite definitively that employers will, to a surprisingly large degree, only raise wages, if they do so at all, as an absolute last resort and almost always with a great deal of reluctance and a great deal of highly vocal complaining. And just as it was the case in the jobless recovery following the Great Recession, the first sign that a material and sustained recovery has taken root is when inflation fever, particularly wage inflation, has sent the nation, especially the right, into an apoplectic panic.

And just like the last recovery, we suspect that the same pattern will play out over the coming months and quarters (and hopefully years): employers needing to fill jobs will struggle to do so via the same methods and at the same pay with the same benefits will eventually exhaust all other means (improving their career portal, increasing their recruitment advertising budgets, expanding their candidate pools, relaxing unnecessarily hiring standards, adding perks, raising signing bonuses, etc.) and eventually, begrudgingly raise wages. As this plays out across the economy, this time around in what seems to be an accelerated fashion, wages will eventually creep up, unemployment will decline, and labor force participation will rise.

Despite the unprecedented backdrop of a global pandemic and an aggressive but highly justified fiscal response, both of which most definitely add some serious wrinkles into the mix, it’s pretty routine stuff which is what prompted such a great piece by Paul Krugman, “The Economy Is Spinning Its Wheels, and About to Take Off” in which he wrote:

The business news these days is full of anxiety. Raw material prices are soaring! Businesses can’t find workers! It’s the 1970s all over again! Chill out, everyone. Mostly we’re just experiencing the economic equivalent of a moment of wheelspin.

What about those reports of labor shortages? Some of this is what always happens after a period of high unemployment: Businesses grow accustomed to having job applicants lined up at their doors, and get cranky when the buyers’ market ends. Small businesses surveyed in early 2015 reported a severe shortage of qualified workers; strange to say, the employment boom that began in 2010 still had another five years to run.

It is, let’s say, hard to shed tears over employers complaining about potential hires who ask, “How much do you pay?”

Still, there is some real evidence, like the number of job openings, that employers are having trouble hiring workers fast enough to meet soaring demand. And issues like child care are probably playing a role. There may also be a certain amount of “you can take this job and shove it” — some workers, especially those already close to retirement, may just not want to go back to the unpleasant, poorly paid work they had before.

Mainly, however, we’re just seeing the problems you’d expect when the economy tries to roar ahead from a standing start, which means that we’re calling on suppliers to ramp up production incredibly fast and expecting employers to quickly attract a large number of new workers. These problems are real, but they’ll mostly resolve themselves in a few months.

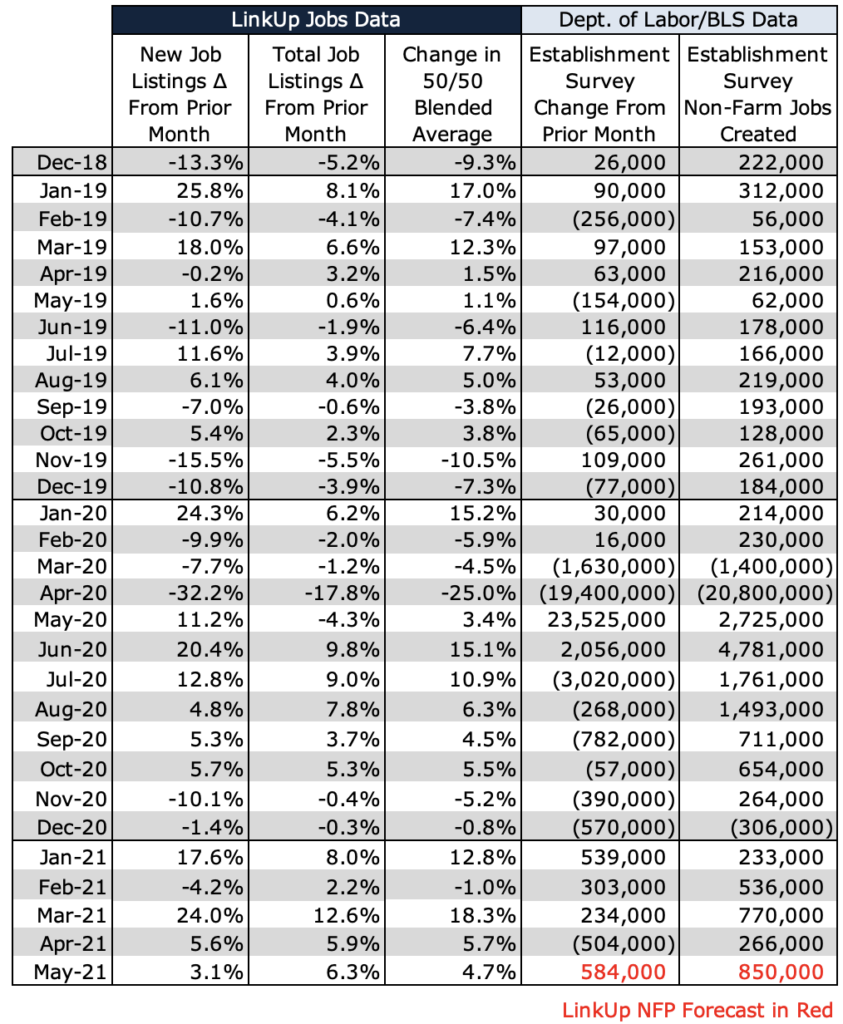

So what can we expect in the coming months, beginning most imminently with May’s Jobs report that comes out on Friday? First, we expect that April’s jobs numbers will be revised upward, potentially quite a bit. And secondly, based on our jobs data for May and the preceding months, we are forecasting net job gains of 850,000 jobs, about 200,000 jobs above consensus estimates.

So to jump into the data, looking at the chart we posted above, total U.S. job openings indexed from company and employer websites globally rose 4% in May to 5.25 million. New job listings rose 3% to 2.04 million and job openings removed from company websites rose 18% to 2.12 million.

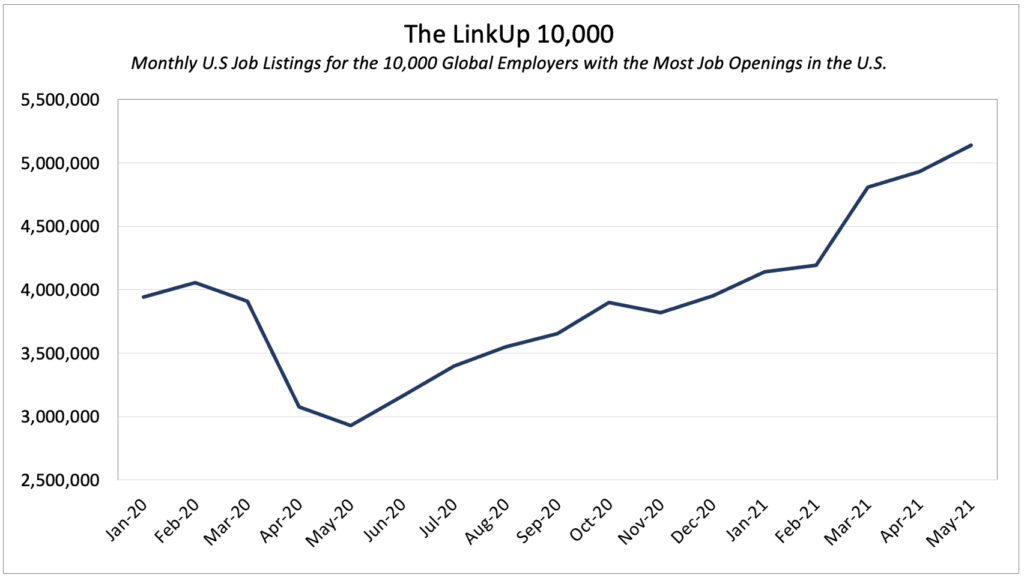

The LinkUp 10,000, a metric that tracks total U.S. job openings for the 10,000 global employers that have the most openings in the U.S., rose 4% to 5.14 million.

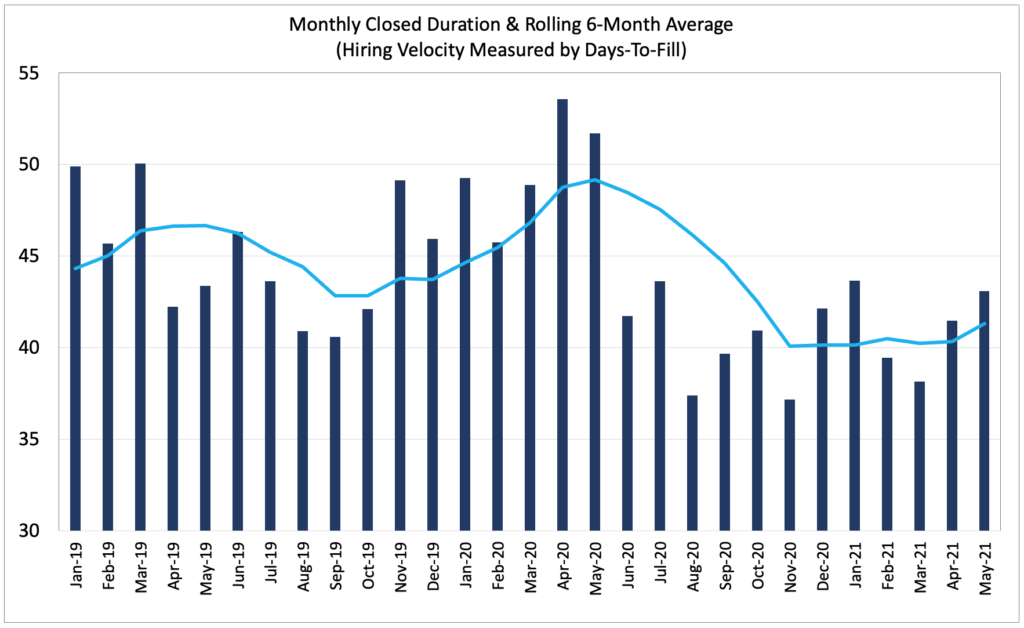

Another metric we track is Monthly Closed Duration which measures the average number of days that openings are posted on employer websites in the U.S. before they are removed, presumably because they are filled. Essentially, duration measures hiring velocity (inversely as fewer days equates to faster hiring), and in May duration rose slightly to 43 days. Interestingly, though, May’s increased duration, when looked at in combination with the large increase in jobs removed (which rose 18% to 2.12 million) could indicate that employers finally filled jobs that had been open for a bit longer than the 90-day average which would indicate a strengthening job market.

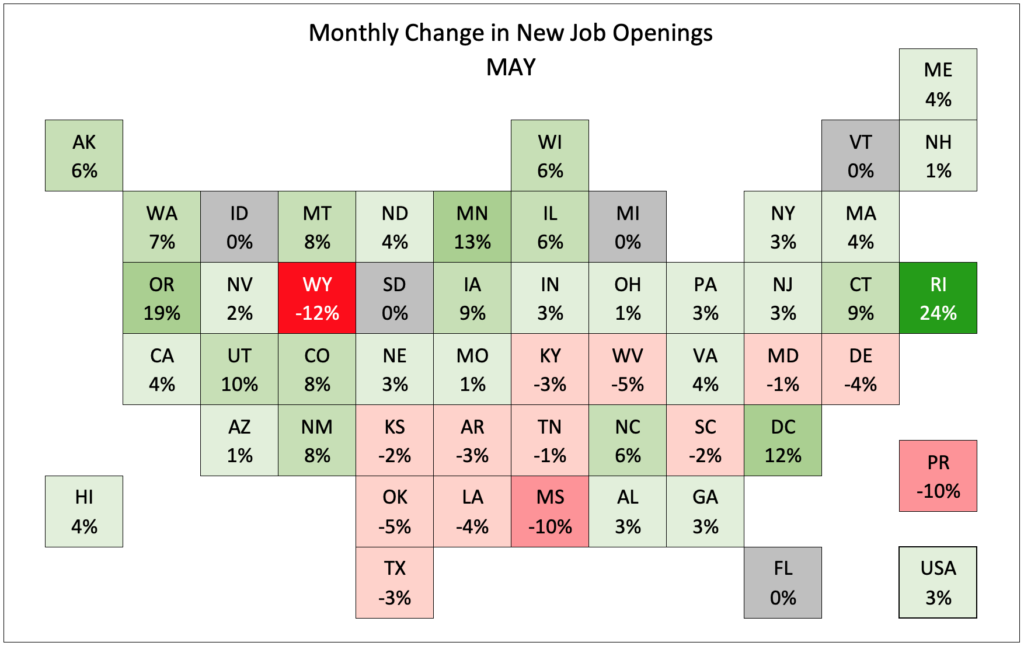

New job openings in the U.S. rose 3%, with variations by state correlating nearly perfectly with the percentage of the state’s population that has been vaccinated.

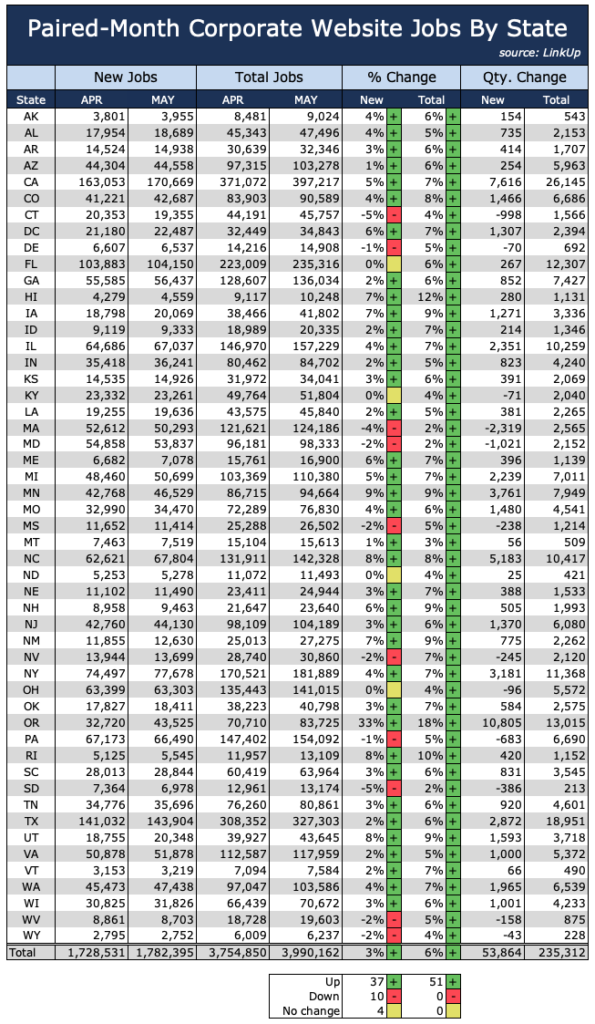

For the purposes of forecasting non-farm payrolls, we use our paired-month data which measures new and total job openings for a common set of companies that were hiring in each of the prior two consecutive months – in this case April and May. Using that data, new and total job openings rose 3% and 6% respectively.

And based on that job data, we are forecasting net job gains of 850,000 in May, well above consensus estimates.

So as Krugman concluded in his May 27th article mentioned above:

“Yes, labor supply issues may have held back April’s job growth, although more recent data suggest a possible rebound. April inflation surprised on the upside, largely because of used car prices. None of this tells you anything at all about how much we should worry about overheating, let alone how much more we should be spending on infrastructure and family support (answer: a lot) or how we should pay for these initiatives (answer: tax corporations and the rich). So as I said, chill out. There is some bad news out there, but most of it is a temporary byproduct of extraordinary good news: The virus is losing, and the economy is winning.”

Insights: Related insights and resources

-

Blog

03.26.2018

LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of 235,000 Jobs In March; Wage Inflation Will Accelerate in Months Ahead

Read full article -

Blog

10.05.2016

The Big Grind: LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain Of 125,000 Jobs in September

Read full article -

Blog

08.05.2016

Despite the Chaos Syndrome, LinkUp Is Forecasting That The U.S. Added 215,000 Jobs In July

Read full article

Stay Informed: Get monthly job market insights delivered right to your inbox.

Thank you for your message!

The LinkUp team will be in touch shortly.