LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of 235,000 Jobs In March; Wage Inflation Will Accelerate in Months Ahead

March: a decline from the robust gains seen in February but still slightly above consensus estimates.

In the forecasting business, particularly one as difficult as non-farm payrolls, it’s difficult to refrain from periodic instances of self-congratulatory gloating. So bear with me for just a minute as I begin this month’s NFP post by turning back to our forecast for February.

A month ago, we forecasted a net gain of 285,000 jobs for February, well above the consensus estimate of just 205,000 jobs.

In addition to the forecast, which was based on the solid rise in job openings on LinkUp’s job search engine in January, we speculated that the strength in the labor market would significantly increase the odds that the Fed would raise rates 4 times this year instead of the 3 increases it has signaled to that point.

In early March, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its initial NFP number for February – a net gain of 313,000 jobs. Shortly thereafter, the Fed raised rates (not a surprise to anyone) and signaled an acceleration of rate increases (a surprise to many) in the future.

It was a particularly gratifying headline jobs number because we were low in our forecast for January and it’s nice to not have to start the year 0-2 (although neither January and February are officially ‘in the books’ until the final BLS revisions).

But as encouraging as the report was to our job market data and our forecast model, it also further emphasized our growing exasperation at the continued lack of accelerating wage inflation in the official numbers, a point to which we’ll return later in this post.

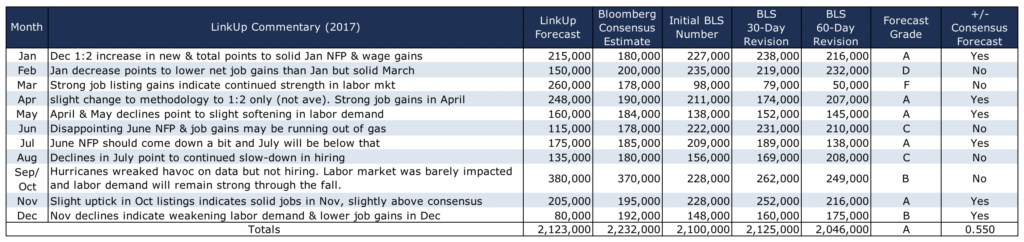

And finally, with February’s Employment Situation Report and the final revisions to December’s non-farm payrolls, we can finally close the book on 2017, a year in which we maintained our above-average forecast record, albeit slightly below the previous 4 years.

As we’ve communicated in the past, our forecast model doesn’t account for weather (admittedly something we’re looking at fixing this year), so we have combined our forecasts for September and October into a single period to remove, to some extent, the impact of the hurricanes last fall and better convey the actual underlying condition of the U.S. labor market through that period. So with that adjustment, we accurately forecasted job gains above or below consensus estimates in 6 of 11 periods for a batting average of .550. Equally as meaningful, we accurately forecasted that, for the year as a whole, job gains would fall short of consensus estimates.

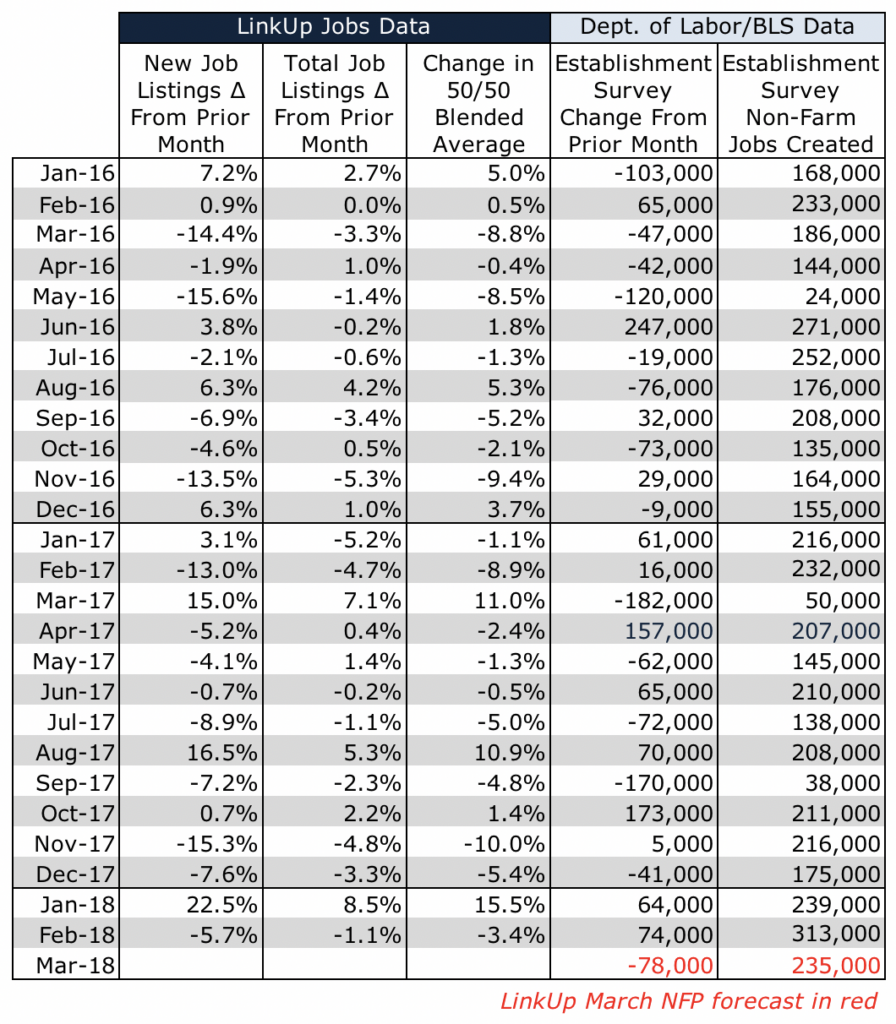

So with the crowing behind us, we’ll turn our attention to our forecast for job gains in March which requires us to look at job listings on LinkUp in February. (Because the best indicator of a job being added to the U.S. economy in the future is when an employer posts an opening on its company career portal, our job openings data, which only includes job market data – ~4.5 million job openings obtained directly from 50,000 employer websites – is highly correlated to job growth in future periods).

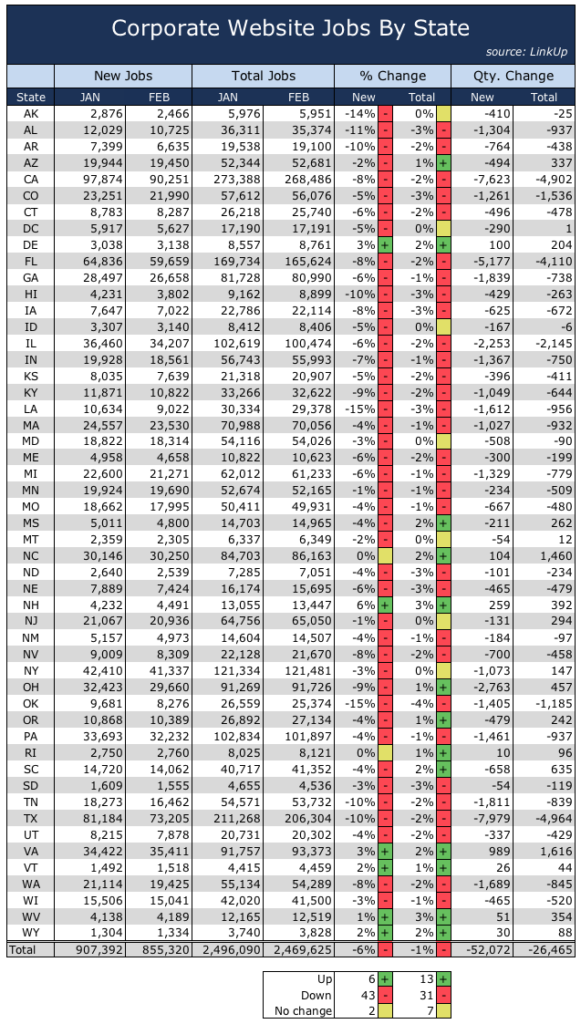

In February, new and total job listings on LinkUp fell 6% and 1% respectively.

As a result of those declines, we are forecasting net job gains of 235,000 for March, a decline from the robust gains seen in February but still slightly above consensus estimates.

So back to the nagging question around wage inflation and why it’s not more evident in the official numbers.

As we mentioned in last month’s post, we first declared that we were in a Full-Employment environment in May of 2016. Last month’s post and the ones from the spring of 2016 provide far more detail around our analysis, but the quick summary is that in Q1/Q2 2016, we started to see in our data and hear from our employer advertisers that broad-based slack in the labor market, across the country and throughout the economy, was disappearing, candidates everywhere were increasingly hard to find, and employers were finally throwing in the towel and admitting, after much reluctance and protracted resistance, that they had to increase costs and raise wages in order to attract candidates – first in the form of higher advertising budgets and then sign-on bonuses and later in hourly wages and annual salaries. That wage growth started in obvious pockets where labor shortages were most acute (transportation, tech, and healthcare) but it has spread, slowly but consistently, to virtually every sector of the economy.

In thinking a lot these days about the strength of the labor market over the past year or so, when we actually entered into a full employment environment, the lackluster pace of wage inflation, and the accuracy (or lack thereof) of our insights into the labor market, I’d make the following observations:

• We were admittedly a bit early in our full employment call

• There was more slack in the labor market than we believed

• The low labor force participation rate was more relevant than we thought

• That slack allowed employers to delay raising wages longer than expected

• Wage growth took longer to spread from specific job categories to the broader economy

• Wage growth didn’t spread to lower-wage jobs until more recently

• As wage growth started to materialize, more entrants into the job market allowed employers to ‘pause’ further salary increases until the slack was absorbed

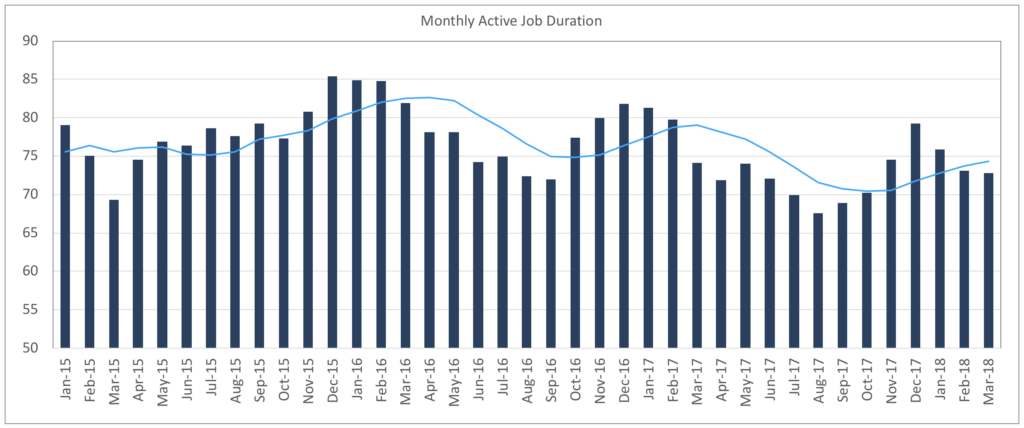

That last point is perfectly represented in the following chart which tracks our Job Duration metric over time. Job Duration measures how long job openings are listed in our job search engine. We track Job Duration for both active jobs as well as closed jobs or jobs that are removed from an employer’s website, most often because they’re filled.

Since Q1 of 2016, when we made our Full Employment call, job duration has shown a very consistent pattern of coming down, rising again slightly, and then coming down further. While there is some seasonality that most definitely comes into play in that pattern, it is also a pattern that one would expect as employers begin to raise wages.

That pattern would be explained thus: Employers resist raising wages as long as possible. It takes longer and longer to fill positions because there are more job openings than applicants in a tightening labor market. When it becomes sufficiently detrimental for an employer to have unfilled jobs, they raise wages. The more attractive pay attracts more applicants, and even draws new people into the labor market. Employers start filling jobs faster and pause any further wage increases until such time as they become necessary again. When the slack is absorbed, jobs once again take longer to fill and the cycle is repeated.

What we missed in expecting wage inflation sooner is that these cycles have taken longer to occur and that with each ‘step’ along the way, more people than expected are coming back into the labor market (long-term unemployed, involuntary part-time workers, members of the gig economy, people who had previously retired, non-traditional workers, etc.). It also could be the case that baby boomers are retiring a bit slower than expected because wages are rising and it is more compelling to stay in the workforce for a bit longer.

The last factor that we’d highlight is perhaps one of the most important:

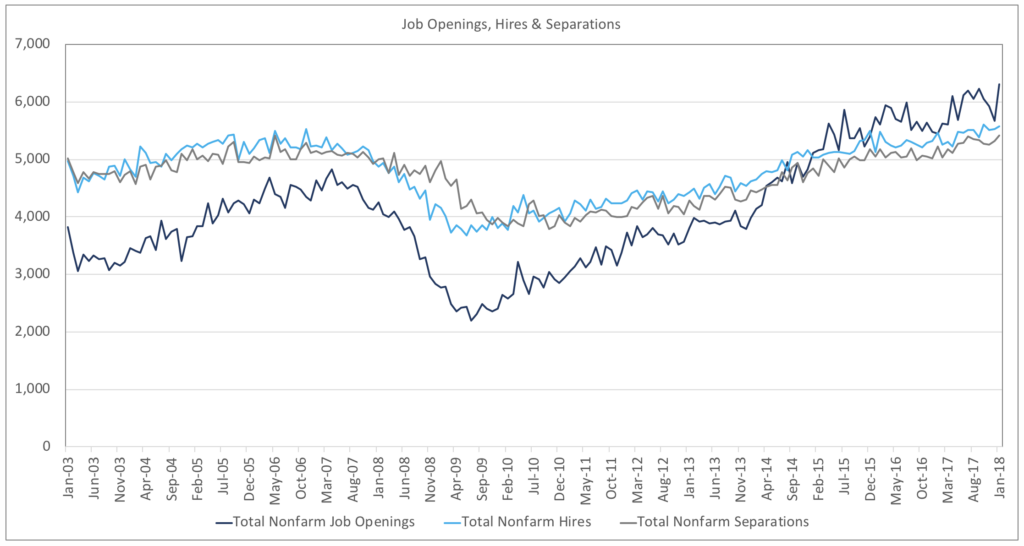

• Separations remained flat for far longer than expected

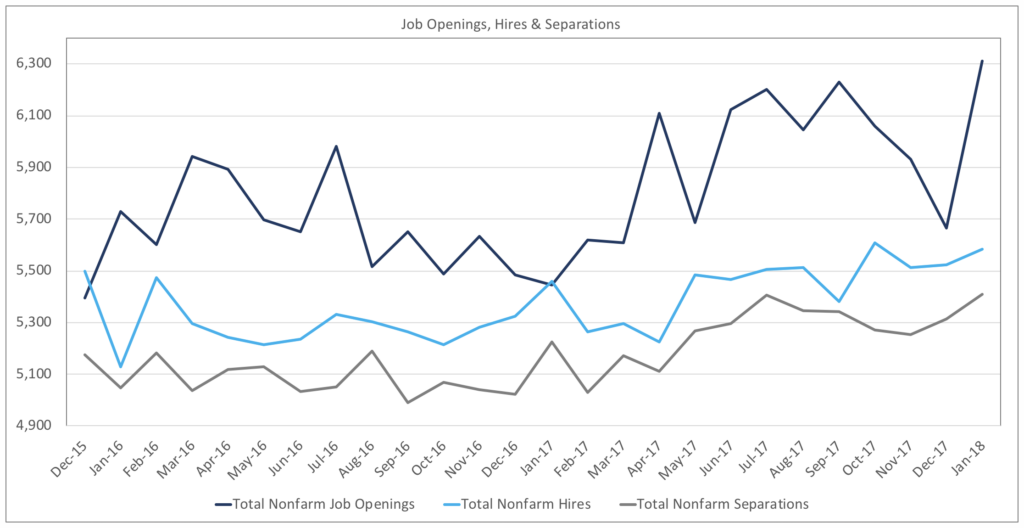

The chart below tracks government data on job openings, hires, and separations for the past 15 years. It wasn’t until late 2014/early 2015 when job openings finally rose above hires, and it wasn’t until Q1 2016 that there was consistent, material separation between job openings and hires. (Again, the Q1 2016 timeframe is material!).

Looking at the same data since January 2016 highlights the fact that separations have remained essentially flat from January 2016 to April 2017, when they started climbing to a level at which they’ve remained since.

What triggers even more wage inflation than an unfilled ‘new’ position is when existing employees leave (more often than not because they were offered a higher-paying job somewhere else) and an employer has to fill that position with higher pay. In a tightening labor market, particularly a full employment labor market, the replacement cost of a departing employee is almost always higher than the pay of that departing worker.

When churn starts rising as people start job hopping for higher pay, wages everywhere start climbing. And when workers leave for higher pay elsewhere, their fellow co-workers get the same idea and start leaving as well. And churn begets more churn, the positively reinforcing cycle starts to accelerate the growth of wages. And while it’s taken longer than expected for the wage inflation flywheel to start turning, there is absolutely no doubt whatsoever that it has started to turn faster and faster. Wage inflation is accelerating.

So again, we’ll stick by our call from May of 2016. That was when, in our estimation, the wage inflation flywheel started turning. Unfortunately, it took longer to start turning at a rate that was detectable in the official numbers. But that has changed in the past few quarters, and significant, measurable inflation is starting to materialize everywhere throughout the labor market and it will inevitably accelerate in the months ahead.

So with that, we’ll double down in our conviction that the biggest labor market story of 2018 will be the ‘surprising,’ perhaps even ‘alarming’ ferocity of wage inflation that materialized sooner than expected, seemingly out of nowhere, sending shockwaves through the stock market.

Just remember, you heard it here first. And lest anyone forget, we’ll be sure to gloat occasionally throughout the year and refer fondly back to our prescient blog post from March 25th.

Insights: Related insights and resources

-

Blog

07.07.2022

Job Openings Dropped 3% in June; LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of Just 265,000 Jobs

Read full article -

Blog

01.07.2021

LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain Of Just 50,000 Jobs In December

Read full article -

Blog

12.03.2020

LinkUp Forecasting Non-Farm Payroll Gain of 490,000 Jobs in November

Read full article -

Blog

04.05.2019

LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of 155,000 Jobs in March

Read full article -

Blog

10.26.2017

The New Abnormal Is Wreaking Havoc on Job Market Forecasts; LinkUp Predicting Net Gain of 120,000 Jobs In October

Read full article -

Blog

02.02.2017

LinkUp Forecasting Solid Job Gains In January and Continued Strength In February

Read full article

Stay Informed: Get monthly job market insights delivered right to your inbox.

Thank you for your message!

The LinkUp team will be in touch shortly.